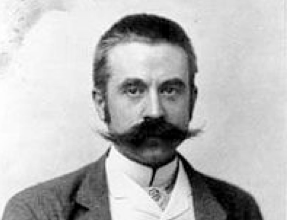

Stanford White

The Gilded Age was a time of pomp and peace and prosperity. Never before were the gaps between the rich and poor so sharply divided as they were in those quiet years before The Great War of 1917. Without personal income tax

to curtail immense fortunes in America’s burgeoning industries, millionaires flourished and paraded their wealth for all the world to see. The magnificent mansions of John D. Rockefeller, J.P. Morgan and Andrew Carnegie stand like faded peacocks along New York’s Fifth Avenue to this day, bearing silent tribute to a luxurious past long faded into time.

Stanford White was born into a life of wealth and privilege on November 9, 1853, the son of the Shakespearean scholar and essayist, Richard Grant White. He was a talented and versatile draftsman who in 1880, joined Charles Follen McKim and William Rutherford Mead in founding McKim, Mead and White, which soon became the most prominent architectural firm in the country. His career was rich and full and varied from designing the summer homes of the Astor’s and The Vanderbilts to such formidable structures as The Washington Square Arch, Madison Square Garden and the New York Herald Building.

Architect in ID

But Stanford White had his dark side and it was darker than most. He led a double life under the very eyes of his adoring wife, Bessie, who chose not to see but could not fail to suffer from her husband’s incessant debauchery. White’s scandalous “parties,” known for their over-sexed, scantily-clad maidens and bubbling French champagne, were often memorialized on the front pages of the tabloids of the day. He was an extrovert, a lavish entertainer with a penchant for young, beautiful women. On the second floor of his tower apartment at Madison Square Garden a red velvet swing dangled from the gold-leaf ceiling, often occupied by the nubile and willing body of one of his countless girls.

One such occupant of the notorious red swing was a seventeen year old red-headed beauty from a small town in Pennsylvania named Evelyn Nesbit. At sixteen, she had posed for the famous Charles Dana Gibson. At seventeen, she worked as a chorus girl in the Floradora review where she caught the roving eye of Stanford White who soon made her his mistress.

According to Nesbit’s own testimony, their affair started one evening at White’s apartment when he slipped “something” into her champagne. When she awoke on his satin bedcovers a few hours later, he informed her that “now she was his.” Despite this lecherous start, their affair lasted for quite a while and White took good financial care of both Miss Nesbit and her mother. But Stanford White eventually grew bored of his conquest and moved on to more nubile territory. They parted amicably and Nesbit married Henry “Harry” Kendall Thaw, the multi-millionaire heir to a railroad and ore fortune from Pittsburgh.

Thaw was a cruel and temperamental bully with a penchant for dog whips. Many an ex-lover knew the pain of his whip for Thaw had a reputation for beating up on women and men as well as defenseless animals. He was used to getting what he wanted when he wanted it at any price. He set his sights on Evelyn Nesbit and would not take no for an answer. He pursued her endlessly, dazzling her with expensive jewels and finery until she finally accepted his proposal of marriage.

Nesbit’s new husband beat her on their honeymoon until she revealed all the details of her former affair with Stanford White. Although she bore him no ill feelings, Thaw vowed to get even with the man who “spoiled” his wife. His deadly rage consumed him and finally erupted at the supper club theater on the roof of Madison Square Garden on the night of June 25, 1906. Concealing a pistol under a heavy overcoat, Thaw followed Stanford White to the opening of the musical review of Mam’zelle Champagne. He approached his table and fired three shots at close range into his face and head. White slumped to the floor, dead. Ironically, he died in a building that he himself had designed just a few years earlier.

Harry Thaw was sent to the Tombs prison where even as a prisoner he enjoyed a life of privilege. His meals were catered every day from Delmonico’s restaurant in the nine months he waited for his trial to begin. After two jury trials, Prosecutor William Travers Jerome failed to make his case for first degree murder and Thaw was found not guilty of the killing of Stanford White by reason of insanity. The case is a landmark in American jurisprudence because it is the first time that a defense attorney (Mr. Delphin Delmas) invoked the plea of temporary insanity and won.

The first thing Thaw did as a free man was divorce Evelyn Nesbit. He returned to a lavish but obscure life and in 1926 wrote a book called ‘The Traitor’ in which he tried to justify his killing of Stanford White. He died in 1947 at the age of 76. Evelyn Nesbit returned to the world of vaudeville where she earned $3,500 dollars per week. She married her stage partner, Jack Clifford, but that soon ended in divorce. As an old woman, she one referred to her life as one that had not been as fortunate as “Stanny’s”, for he had died fairly young and at the peak of his talents. She herself died as a faded beauty in a nursing home in 1966 at the age of 81. Even in death, it seems, we are not equal.

profile

Name Stanford White Nationality American Birth date November 9, 1853 Birth place New York City, New York, USA Date of death June 25, 1906 (aged 52) Place of death Manhattan, New York City, New York State

His Murder

Murder on the Rooftop Garden

In the breezy heat of summer, June 25, 1906, a group of wealthy revelers gathered on the roof of the old Madison Square Garden (the gilded building that was actually located at Madison Square) to watch the premiere of a mediocre musical review. The women wore elaborate, beaded dresses and feathered hats. The men, dressed in dapper suits and many sporting sculptured facial hair, smoked cigars. The good-humored crowd paid some attention to the chorus girls and singers, but also actively socialized. Thus, the performers struggled to be heard above the din of voices and clinking glasses.

One man, a jovial fifty-something redhead with a fashionable moustache, appeared mesmerized by the showgirls. He sat near the front of the stage by himself, which was unusual for this highly social man. The man applauded wildly, grinning and winking at the virginal-looking girls who sang a lively song about dueling.

Meanwhile, another, younger man moved through the crowd towards the older man. This handsome, glowering figure drew a slight amount of attention by wearing a black overcoat in the heat of summer. Earlier in the evening the hatcheck girl had made numerous attempts to check the coat, but the man had steadfastly refused.

Still, the crowd paid little attention to the eccentrically dressed man, assuming he sought out friends. Most recognized him, if they did not know him personally. A couple of people noticed him approach the older man's table, only to fall back for a few moments and stare. As a performer broke into a song called "I Could Love A Million Girls," the younger man finally strode over to table of the older man.

From beneath the overcoat, the young man produced a pistol and fired three close range shots directly into the face of the older man. The victim's elbow, suddenly inert, slid off the table, which overturned with a thump and a clatter. The body slumped to the floor.

At first, there was awkward silence. Then, there came a bit of terse laughter — as many assumed the spectacle to be part of the show. Elaborate practical jokes were commonplace among New York society. As the mangled and bloody face, blackened with powder burns, became visible, the screams began.

The killer, showing little emotion, removed the rest of the bullets from his pistol. As he moved towards the exit, he held the gun aloft to indicate he had ceased shooting, but this gesture did no good. Panic ensued, and people raced for the doors. The theatre manager pleaded for calm and absurdly bade the show to go on, but the orchestra petered out after a half-hearted attempt to play. The terrified chorus girls could not sing. Someone threw a white tablecloth over the victim, still flopped across the floor next to his overturned table. When blood soaked through the sheet, the man hastily added a second cloth.

Meanwhile, the killer found his confused party of friends standing by the elevators. A stunning, copper-curled woman in a white eyelet dress saw the pistol, still held aloft in her husband's hand.

"Good God, Harry! What have you done?" asked Evelyn Nesbit Thaw.

"All right dearie," replied Harry Thaw of Pittsburgh calmly, "I have probably saved your life."

About Stanford White